COMPLEX NUMBER - 7 (Rotation Theorem)

GEOMETRY OF COMPLEX NUMBERS

1. Distance between two complex numbers $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ is $\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|$

Section formula

2. Two points $P \& Q$ have affixes $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ respectively in the argand plane, then the affix of a point $\mathrm{R}$ dividing $\mathrm{PQ}$ is the ratio $\mathrm{m}: \mathrm{n}$

i. internally is $\frac{m z _{2}+n z _{1}}{m+n}$

ii. externally is $\frac{m z _{2}-n z _{1}}{m-n}$

iii. If $R$ is the mid point $P Q$, then affix of $R$ is $\frac{Z _{1}+Z _{2}}{2}$

Special points of a triangle

3.

| Segment/Line | Figure | point of concurrency | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perpendicular bisectors |  |

Circumcentre (Equidistant from vertices) | $\mathrm{z} _{3}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1} \sin 2 \mathrm{~A}+\mathrm{z} _{2} \sin 2 \mathrm{~B}+\mathrm{z} _{3} \sin 2 \mathrm{C}}{\sin 2 \mathrm{~A}+\sin 2 \mathrm{~B}+\sin 2 \mathrm{C}}$ $\frac{\sum\left|\mathrm{z} _{1}\right|^{2}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)}{\sum \overline{\mathrm{z}} _{1}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)}$ |

| Angle bisectors from the sides) |  |

Incentre (equidistant to the sides) | $z _{3}=\frac{a z _{1}+b z _{2}+c z _{3}}{a+b+c}$ $a=\left|z _{2}-z _{3}\right|, b=\left|z _{1}-z _{3}\right|$, $c=\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|$ |

| Medians |  |

Centroid ( distance from vertex to G is $\frac{2}{3}$ of total median) | $\mathrm{G} _{\mathrm{z}}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1}+\mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{3}}{3}$ |

| Altitudes |  |

Orthocentre (can be inside, outside or on the right angle) | $\mathrm{Z} _{\mathrm{H}}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1}(\tan \mathrm{A})+\mathrm{z} _{2}(\tan \mathrm{B})+\mathrm{z} _{3}(\tan \mathrm{C})}{\tan \mathrm{A}+\tan \mathrm{B}+\tan \mathrm{C}}$ $\frac{\sum \overline{\mathrm{Z}} _{1}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{3}-\mathrm{z} _{1}\right)}{\sum \mathrm{z} _{1}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)}$ |

4. Area of the triangle with vertices $\mathrm{z} _{1}, \mathrm{z} _{2}$ & $\mathrm{z} _{3}$ is $\frac{1}{4}\left|\overline{\mathrm{z}} _{1}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)\right|$

Equilateral triangle

5. In equilateral $\triangle \mathrm{ABC}$, where the vertices are given by $\mathrm{z} _{1}, \mathrm{z} _{2}, \mathrm{z} _{3}$ and the circumcentre is $\mathrm{z} _{0}$,

i. $z _{1}^{2}+z _{2}^{2}+z _{3}^{2}=3 z _{0}^{2}$

ii. $\mathrm{z} _{1}^{2}+\mathrm{z} _{2}^{2}+\mathrm{z} _{3}^{2}=\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{2} \mathrm{z} _{3}+\mathrm{z} _{3} \mathrm{z} _{1}$

iii. $\frac{1}{z _{1}-z _{2}}+\frac{1}{z _{2}-z _{3}}+\frac{1}{z _{3}-z _{1}}=0$

6. If $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}, z _{4}$ are vertices of a parallelogram if and only if $z _{1}+z _{3}=z _{2}+z _{4}$.

7. If $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}, z _{4}$ are vertices of a square in the same order, then

i. $z _{1}+z _{3}=z _{2}+z _{4}$

ii. $\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|=\left|z _{2}-z _{3}\right|=\left|z _{3}-z _{4}\right|=\left|z _{4}-z _{1}\right|$

iii. $\left|z _{1}-z _{3}\right|=\left|z _{2}-z _{4}\right|$

iv. $\frac{\left|z _{1}-z _{3}\right|}{\left|z _{2}-z _{4}\right|}$ is purely imaginary

8. Equation of the straight line joining $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ is i. $ \arg \left(\frac{z-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)=\pi$ or 0 i.e. $\left(\frac{z-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)$ must be real i.e. $\frac{z-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}=\frac{\bar{z}-\bar{z} _{1}}{\bar{z} _{2}-\bar{z} _{1}}$ or

$\left|\begin{array}{lll}\mathrm{z} & \overline{\mathrm{Z}} & 1 \\ \mathrm{z} _{1} & \overline{\mathrm{Z}} _{1} & 1 \\ \mathrm{z} _{2} & \overline{\mathrm{Z}} _{2} & 1\end{array}\right|=0$ (non-parametric form)

ii. $ \mathrm{z}=\lambda \mathrm{z} _{1}+(1-\lambda) \mathrm{z} _{2}$ (parametric form)

iii. General equation of $a$ line is $\bar{a} z+a \bar{z}+b=0$ where $b \in R$.

Note: Condition for 3 points $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}$ to be collinear is that $\arg \frac{z _{3}-z _{1}}{z _{3}-z _{2}}=0$ or $\pi$

Two points $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ lie on the same side or opposite side of the line $\bar{a} \bar{z}+a \bar{z}+b=0$ according as $\overline{\mathrm{a}} \mathrm{z} _{1}+\mathrm{a} \overline{\mathrm{z} _{1}}+\mathrm{b}$ and $\overline{\mathrm{a}} \mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{a} \overline{\mathrm{z} _{2}}+\mathrm{b}$ have same sign or opposite sign.

9. Slope of the line segment joining $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ is $\frac{z _{1}-z _{2}}{z _{1}-z _{2}}$. Two lines with slopes $\omega _{1} \& \omega _{2}$ are

(a). perpendicular if $\omega _{1}+\omega _{2}=0$

(b). parallel if $\omega _{1}=\omega _{2}$

10. Length of the perpendicular from $z _{1}$ to $\bar{a} \bar{z}+\bar{a} z+b=0$ is $\frac{a \overline{z _{1}}+\bar{a} z _{1}+b}{2|a|}$

11. Equation of the perpendicular bisector of the line segment joining $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ is $\mathrm{z}\left(\overline{\mathrm{z}} _{1}-\overline{\mathrm{z}} _{2}\right)+\overline{\mathrm{z}}\left(\mathrm{z} _{1}-\mathrm{z} _{2}\right)=\left|\mathrm{z} _{1}\right|^{2}-\left|\mathrm{z} _{2}\right|^{2}$

Equation of a circle

12. i. $\left|z-z _{0}\right|=r$ or $z \bar{z}-z _{0} \bar{z}-\overline{z _{0}} z+z _{0} \overline{z _{0}}-r^{2}=0$ where $z _{0}$ the centre $\& r$ is the radius

ii. $\left|z-z _{1}\right|^{2}+\left|z-z _{2}\right|^{2}=\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|^{2}$ (circle described on the line joining $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ as diameter)

iii. General equation of $a$ circle is $\overline{z z}+\bar{a} \bar{z}+\bar{a} z+b=0$ where $b \in R$. Centre is $-a$ and radius is $\sqrt{a \bar{a}-b}$

- Four points $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}, z _{4}$ are concyclic if and only if $\frac{\left(z _{1}-z _{3}\right)\left(z _{2}-z _{4}\right)}{\left(z _{1}-z _{4}\right)\left(z _{2}-z _{3}\right)}$ is purely real.

Loci in complex plane

13. i. $\left|z-z _{0}\right|=r$ circle with centre $z _{0} \&$ radius $\mathrm{r}$.

$1\left|z-z _{0}\right|<r$ : interior of this circle

$1\left|z-z _{0}\right|>r$ : exterior of this circle

$1\left|z-z _{1}\right|=\left|z-z _{2}\right|$

perpendicular bisector of the segment joining $z _{1} \& z _{2}$

iii. $\left|z-z _{1}\right|+\left|z-z _{2}\right|=k\left\{\begin{array}{l}\text { is an ellipse if } \mathrm{k}>\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right| \\ \text { is a straight line if } k=\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|\end{array}\right.$

iv. $\left|z-z _{1}\right|-\left|z-z _{2}\right|=k\left\{\begin{array}{l}\text { is a hyperbola if } k<\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right| \\ \text { is a straight line if } k=\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|\end{array}\right.$

v. argument $\left(\frac{z-z _{1}}{z-z _{2}}\right)=a, a$ fixed angle is a circle.

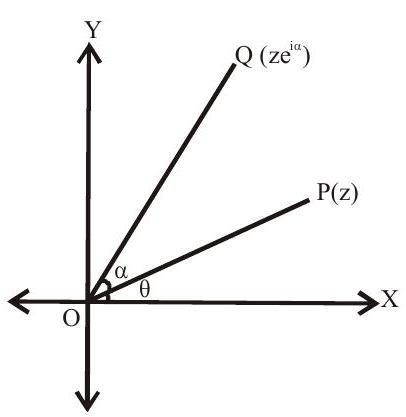

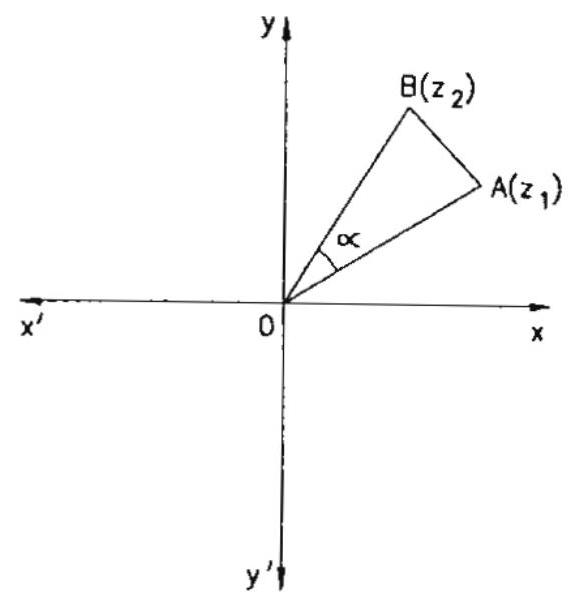

14. Complex number as a rotation arrow in the argand plane.

Let $\mathrm{z}=\mathrm{re}^{\mathrm{i} \theta}$

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{OP}=\mathrm{r} \& \angle \mathrm{XOP}=\theta$

$\mathrm{ze}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha}$ is a complex number whose modulus is $\mathrm{r}$ and argument $\angle \mathrm{XOP}=\theta+\alpha$. To obtain $\mathrm{ze}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha}$, rotate $\mathrm{OP}$ through an angle $\alpha$ in anticlockwise direction.

Note: Let $\mathrm{z} _{1} \& \mathrm{z} _{2}$ be two complex represented by $\mathrm{P} \& \mathrm{Q}$ such that $\angle \mathrm{POQ}=\alpha . \mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \omega}$ is a vector of magnitude $\mathrm{OP}=\left|\mathrm{z} _{1}\right|$ along $\overline{\mathrm{OQ}} \cdot \frac{\mathrm{z} _{1}}{\left|\mathrm{z} _{1}\right|} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha}$ is a unit vector along $\overline{\mathrm{O}} \mathrm{Q}$.

$\therefore $ A vector of magnitude $\left|z _{2}\right|=$ OQ units is given by $\left|z _{2}\right| \frac{z _{1}}{z _{1} \mid} e^{i \omega}$

i.e. $ z _{2}=\frac{\left|z _{2}\right|}{\left|z _{1}\right|} z _{1} e^{i \omega}$

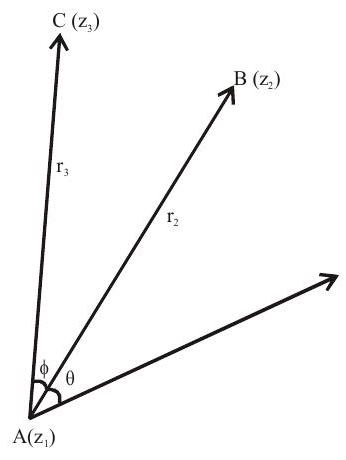

Note: general formula for rotation

If $A B$ is rotated to $A C$ but $A B \neq A C$, then

$\frac{\mathrm{z} _{3}-\mathrm{z} _{1}}{\mathrm{r} _{3}}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{1}}{\mathrm{r} _{2}} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \varphi}$

$1$ Multiplication of $\mathrm{z}$ with $\mathrm{i}$ rotates the vector $\mathrm{z}$ through a right angle in anticlockwise direction $\left(\because \mathrm{i}=1 \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / 2}\right)$

$1$ Multiplication of $z$ by -1 rotates the vector $z$ through an angle of $180^{\circ}$ in anticlockwise direction.

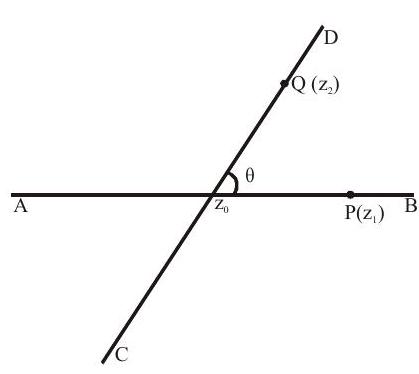

$1$ Let $\mathrm{AB} \& \mathrm{CD}$ intersect at $\mathrm{z} _{0}$. Let $\mathrm{P}\left(\mathrm{z} _{1}\right) \& \mathrm{Q}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}\right)$ be two points on $A B \& C D$. Then the angle $\theta$ is given by $\theta=\arg \left(\frac{z _{2}-z _{0}}{z _{1}-z _{0}}\right)=\arg \left(z _{2}-z _{0}\right)-\arg \left(z _{1}-z _{0}\right)$

Solved Examples

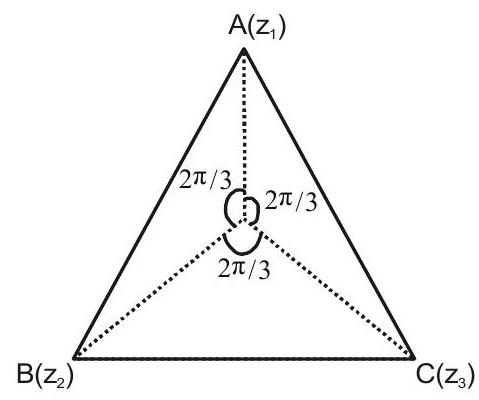

1. If $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}$ are the vertices of an equilateral triangle having its circumcentre at the origin such that $z _{1}=1+i$, find $z _{2}$ and $z _{3}$.

Show Answer

Solution: Clearly, $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}$ and $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}}$ are obtained by rotating $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}$ through $2 \pi / 3$ and $4 \pi / 3$ respectively.

$\therefore \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / / 3}$ and, $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} 4 \pi / 3}$

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{z} _{2}=\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} 2 \pi / 3}$ and, $\mathrm{z} _{3}=\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} 4 \pi / 3}$

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{z} _{2}=(1+\mathrm{i})(\cos 2 \pi / 3+\mathrm{i} \sin 2 \pi / 3)$ and, $\mathrm{z} _{3}=(1+\mathrm{i})(\cos 4 \pi / 3+\mathrm{i} \sin 4 \pi / 3)$

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{z} _{2}=(1+\mathrm{i})(-1 / 2+\mathrm{i} \sqrt{3} / 2)$ and $\mathrm{z} _{3}=(1+\mathrm{i})(-1 / 2-\mathrm{i} \sqrt{3} / 2)$

$\Rightarrow \mathrm{z} _{2}=-\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}+1}{2}\right)+\mathrm{i}\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}-1}{2}\right)$ and $\mathrm{z} _{3}=-\left(\frac{1-\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)-\mathrm{i}\left(\frac{1+\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)$

Example: 2 Let $\mathrm{z} _{1}$ and $\mathrm{z} _{2}$ are roots of the equation $\mathrm{z}^{2}+\mathrm{pz}+\mathrm{q}=0$, where the coefficients $\mathrm{p}$ and $\mathrm{q}$ may be complex numbers. Let $A$ and $B$ represent $z _{1}$ and $z _{2}$ in the complex plane. If $\angle A O B=\alpha \neq 0$ and $\mathrm{OA}=\mathrm{OB}$, where $\mathrm{O}$ is origin, prove that $\mathrm{p}^{2}=4 \mathrm{q} \cos ^{2} \alpha / 0$.

Show Answer

Solution: Since $z _{1}$ and $z _{2}$ are roots of the equation $z^{2}+p z+q=0$

$\therefore \mathrm{z} _{1}+\mathrm{z} _{2}=-\mathrm{p}$ and $\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{z} _{2}=\mathrm{q}$

Since $\mathrm{OA}=\mathrm{OB}$. So, $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}$ is obtained by rotating $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}$ in

anticlockwise sense through angle $\alpha$.

$ \begin{aligned} & \therefore \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}=\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \mathrm{z} _{2}=\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \frac{z _{2}}{z _{1}}=\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha \\ & \Rightarrow \frac{\mathrm{z} _{2}}{\mathrm{z} _{1}}+1=1+\cos \alpha+\mathrm{i} \sin \alpha \end{aligned} $

$ \begin{aligned} & \Rightarrow \frac{z _{2}+z _{1}}{z _{1}}=2 \cos \frac{\alpha}{2}\left(\cos \frac{\alpha}{2}+i \sin \frac{\alpha}{2}\right)=2 \cos \frac{\alpha}{2} e^{i \alpha / 2} \\ & \Rightarrow \frac{z _{2}+z _{1}}{z _{1}}=2 \cos \frac{\alpha}{2} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha / 2} \\ & \Rightarrow \left(\frac{\mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{1}}{\mathrm{z} _{1}}\right)^{2}=4 \cos ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \left(\frac{\mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{1}}{\mathrm{z} _{1}}\right)^{2}=4 \cos ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2}\left(\frac{\mathrm{z} _{2}}{\mathrm{z} _{1}}\right) \\ & \Rightarrow \left(\mathrm{z} _{2}+\mathrm{z} _{1}\right)^{2}=4 \mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{z} _{2} \cos ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} \\ & \Rightarrow (-\mathrm{p})^{2}=4 \mathrm{q} \cos ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} \\ & \Rightarrow \mathrm{p}^{2}=4 \mathrm{q} \cos ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} \end{aligned} $

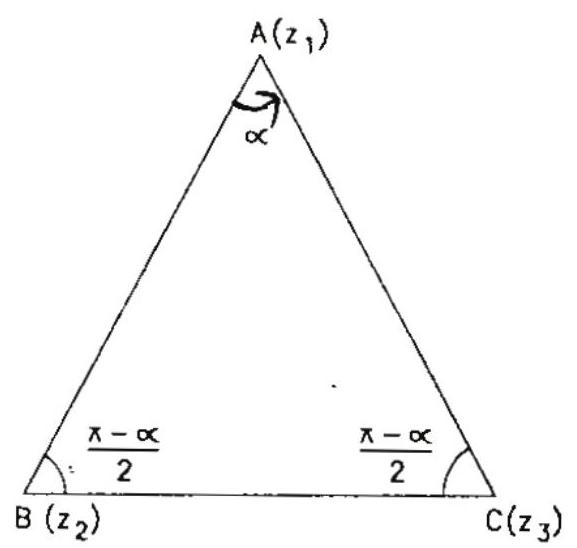

Example: 3 If the points $\mathrm{A}, \mathrm{B}, \mathrm{C}$ represent the complex numbers $\mathrm{z} _{1}, \mathrm{Z} _{2}, \mathrm{z} _{3}$ respectively and the angles of the $\triangle \mathrm{ABC}$ at $\mathrm{B}$ and $\mathrm{C}$ are both $\left(\frac{\pi-\alpha}{2}\right)$. Prove that $\left(\mathrm{z} _{3}-\mathrm{z} _{2}\right)^{2}=4\left(\mathrm{z} _{3}-\mathrm{z} _{1}\right)\left(\mathrm{z} _{1}-\mathrm{z} _{2}\right) \sin ^{2}\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)$.

Show Answer

Solution: We have,

$ \begin{aligned} & \angle \mathrm{B}=\angle \mathrm{C}=\frac{\pi-\alpha}{2} \\ & \therefore \quad \mathrm{A}=\pi-\left(\frac{\pi-\alpha}{2}+\frac{\pi-\alpha}{2}\right)=\alpha \end{aligned} $

Since $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}$ is obtained by rotating $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}$ through angle $\alpha$.

$ \begin{aligned} & \therefore \quad \overrightarrow{A C}=\overrightarrow{A B} e^{i \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad\left(z _{3}-z _{1}\right)=\left(z _{2}-z _{1}\right) e^{i \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z _{3}-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}=\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha \\ & \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z _{3}-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}-1=-1+\cos \alpha+i \sin \alpha \\ & \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}=-2 \sin ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2}+2 i \sin \frac{\alpha}{2} \cos \frac{\alpha}{2} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}=2 i \sin \frac{\alpha}{2}\left(\cos \frac{\alpha}{2}+i \sin \frac{\alpha}{2}\right) \\ & \Rightarrow \quad \frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}=2 i \sin \frac{\alpha}{2} e^{i \alpha / 2} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad\left(\frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)^{2}=4 i^{2} \sin ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2}\left(e^{i \alpha / 2}\right)^{2} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad\left(\frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)^{2}=-4 \sin ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} e^{i \alpha} \\ & \Rightarrow \quad\left(\frac{z _{3}-z _{2}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)^{2}=-4 \sin ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2}\left(\frac{z _{3}-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right) \\ & \Rightarrow \quad\left(z _{3}-z _{2}\right)^{2}=4\left(z _{3}-z _{1}\right)\left(z _{1}-z _{2}\right) \sin ^{2} \frac{\alpha}{2} \end{aligned} $

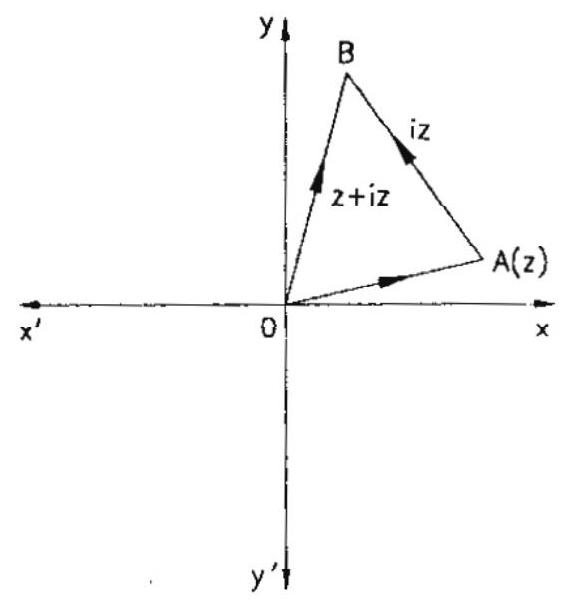

Example: 4 Show that the area of the triangle on the Argand plane formed by the complex numbers $z$, iz and $z+i z$ is $\frac{1}{2}|z|^{2}$

Show Answer

Solution: We have, $\mathrm{iz}=\mathrm{ze} \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / 2}$

This implies that iz is the vector obtained by rotating vector

$\mathrm{z}$ in anticlockwise direction through $90^{\circ}$. Therefore, $\mathrm{OA} \perp \mathrm{AB}$. So,

Area of $\triangle \mathrm{OAB}=\frac{1}{2} \mathrm{OA} \times \mathrm{OB}$

$=\left.\quad \frac{1}{2}|z| i z\left|=\frac{1}{2}\right| z\right|^{2}$.

Example: 5 Let $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}$ be the affixes of the vertices $A, B$ and $C$ respectively of a $\triangle A B C$. Prove that the triangle is equilateral if $z _{1}^{2}+z _{2}^{2}+z _{3}^{2}=z _{1} z _{2}+z _{2} z _{3}+z _{3} z _{1}$.

Show Answer

Solution: First, let $z _{1}, z _{2}, z _{3}$ be the affixes of the vertices $A, B, C$ of an equilateral triangle $A B C$.

Then, we have to prove that $z _{1}^{2}+z _{2}^{2}+z _{3}^{2}=z _{1} z _{2}+z _{2} z _{3}+z _{3} z _{1}$.

Since $\triangle \mathrm{ABC}$ is an equilateral triangle.

Therefore,

$\mathrm{AB}=\mathrm{BC}=\mathrm{AC}$ and $\angle \mathrm{A}=\angle \mathrm{B}=\angle \mathrm{C}=\pi / 3$.

Clearly, $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}$ can be obtained by rotating $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}$ in anticlockwise sense through $60^{\circ}$.

$\therefore \quad \mathrm{z} _{3}-\mathrm{z} _{1}=\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{1}\right) \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / 3}………(1)$

Also $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{BC}}$ can be obtained by rotating $\overrightarrow{\mathrm{BA}}$ by $\frac{\pi}{3}$ anticlockwise

$\therefore \quad \mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}=\left(\mathrm{z} _{1}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right) \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / 3}……..(2)$

From (1) and (2)

$\left(\frac{z _{3}-z _{1}}{z _{2}-z _{1}}\right)=\left(\frac{z _{2}-z _{3}}{z _{1}-z _{3}}\right)$

Solving we get $z _{1}^{2}+z _{2}^{2}+z _{3}^{2}=z _{1} z _{2}+z _{2} z _{3}+z _{3} z _{1}$.

Practice questions

1. The complex number $z=x+$ iy which satisfy the equation $\left|\frac{z-5 i}{z+5 i}\right|=1$ lie on

(a). the $\mathrm{x}$-axis

(b). the straight line $y=5$

(c). a circle passing through the origin

(d). none of these

Show Answer

Answer: (a)2. Let $z$ & w be two complex numbers such that $|z| \leq 1,|w| \leq 1$ and $|z+i w|=|z-i w|=2$ then $z=$

(a). 1 or $\mathrm{i}$

(b). i or $-\mathrm{i}$

(c). $1$ or $-1$

(d). $i$ or $-1$

Show Answer

Answer: (c)3. Let $z _{1} \& z _{2}$ be the nth roots of unity which subtend a right angle at the origin, then $n$ must be of the form (where $k \in z$ )

(a). $4 \mathrm{k}+1$

(b). $4 \mathrm{k}+2$

(c). $4 \mathrm{k}+3$

(d). $4 \mathrm{k}$

Show Answer

Answer: (d)4. The complex number $\mathrm{z} _{1}, \mathrm{z} _{2} \& \mathrm{z} _{3}$ satisfying $\left(\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1}-\mathrm{z} _{3}}{\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}}\right)=\frac{1-\mathrm{i} \sqrt{3}}{2}$ are the vertices of a triangle which is

(a). of area zero

(b). right angled isosceles

(c). equilateral

(d). obtuse-angled isosceles

Show Answer

Answer: (c)5. For all complex numbers $z _{1}, z _{2}$ satisfying $\left|z _{1}\right|=12$ and $\left|z _{2}-3-4 i\right|=5$, the minimum value of $\left|z _{1}-z _{2}\right|$ is

(a). $0$

(b). $2$

(c). $7$

(d). $17$

Show Answer

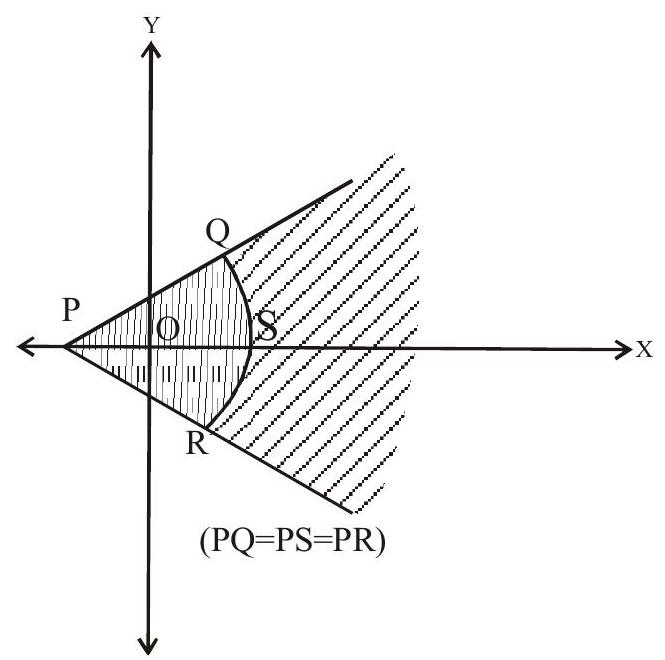

Answer: (b)6. The shaded region where $\mathrm{P}=(-1,0), \mathrm{Q}=(-1+\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2}), \mathrm{R}=(-1+\sqrt{2},-\sqrt{2}), \mathrm{S}=(1,0)$ is represented by

(a). $|z+1|>2,|\arg (z+1)|<\frac{\pi}{4}$

(b). $|\mathrm{z}+1|<2,|\arg (\mathrm{z}+1)|<\frac{\pi}{2}$

(c). $|z+1|>2,|\arg (z+1)|>\frac{\pi}{4}$

(d). $|z-1|<2,|\arg (z+1)|>\frac{\pi}{2}$

Show Answer

Answer: (a)7. A man walks a distance of 3 units from the origin towards the North-East $\left(\mathrm{N} 45^{\circ} \mathrm{E}\right)$ direction. Form there, he walks a distance of 4 units towards the North-West $\left(\mathrm{N} 45^{\circ} \mathrm{W}\right)$ direction to reach a point $\mathrm{P}$. Then the position of $\mathrm{P}$ is the Argand plane is

(a). $ 3 \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} \pi / 4}+4 \mathrm{i}$

(b). $(3-4 \mathrm{i}) \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} / 4}$

(c). $(4+3 i) e^{i \pi / 4}$

(d). $(3+4 \mathrm{i}) \mathrm{e}^{\mathrm{i} / 4}$

Show Answer

Answer: (d)8. A particle $P$ starts from the point $z _{0}=1+2$ i. It moves first horizontally away from origin by 5 units and then vertically away from origin by 3 units to reach a point $z _{1}$. From $z _{1}$ the particle moves $\sqrt{2}$ units in the direction of the vector $\hat{i}+\hat{j}$ and then it moves through an angle $\frac{\pi}{2}$ in anticlockwise direction on a circle with centre at origin to reach a point $z _{2}$. The point $z _{2}$ is given by

(a). $6+7 \mathrm{i}$

(b). $-7+6 \mathrm{i}$

(c). $ 7+6 \mathrm{i}$

(d). $-6+7 \mathrm{i}$

Show Answer

Answer: (d)9. Match the following

| Column I | Column II |

|---|---|

| (a). The set of points $z$ satisfying $\mid z-i\mid z\mid=\mid z+i\mid z\mid \mid$ is contained in or equal to | p. an ellipse with eccentricity $4 / 5$ |

| (b). The set of points $z$ satisfying $\mid z+4\mid +\mid z-4\mid=0$ is contained in or equal to | q. the set of points $z$ satisfying $im (z)=0$ |

| (c). If $\mid w\mid=2$, then the set of points $\mathrm{z}=\mathrm{w}-\frac{1}{\mathrm{w}}$ is contained in or equal to | r. the set of points $z$ satisfying $\mid\operatorname{Im}(z)\mid \leq 1$ |

| (d). If $\mid w\mid=1$, then the set of points | s. the set of points satisfying $|\operatorname{Re}(\mathrm{z})| \leq 2$ |

| t. the set of points $z$ satisfying $\mid z\mid\leq 3$ |

Show Answer

Answer: a $\rarr$ q, r ; b $\rarr$ p; c $\rarr$ p, s, t; d $\rarr$ q, r, s, t10. If $a, b, c$ and $u, v, w$ are complex numbers representing the vertices of two triangles such that $\mathrm{c}=(1-\mathrm{r}) \mathrm{a}+\mathrm{rb}, \mathrm{w}=(1-\mathrm{r}) \mathrm{u}+\mathrm{rv}$, where $\mathrm{r}$ is a complex number, then the two triangles

(a). have the same area

(b). are similar

(c). are congruent

(d). none of these

Show Answer

Answer: (b)11. The locus of the centre of a circle which touches the circles $\left|z-z _{1}\right|=a$ and $\left|z-z _{2}\right|=b$ externally is

(a). an ellipse

(b). a hyperbola

(c). circle

(d). none of these

Show Answer

Answer: (b)12. If one of the vertices of the square circumscribing the circle $|z-1|=\sqrt{2}$ is $2+i \sqrt{3}$, then which of the following can be a vertex of it?

(a). $1-\sqrt{3} \mathrm{i}$

(b). $-\sqrt{3} \mathrm{i}$

(c). $1+\sqrt{3} \mathrm{i}$

(d). none of these

Show Answer

Answer: (a, b, c)13. Read the passage and answer the following questions:

$\mathrm{A}\left(\mathrm{z} _{1}\right), \mathrm{B}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}\right), \mathrm{C}\left(\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)$ are the vertices a triangle inscribed in the circle $|\mathrm{z}|=2$. Internal angle bisector of the angle A meets the circum circle again at $\mathrm{D}\left(\mathrm{z} _{4}\right)$.

i. Complex number representing point $\mathrm{D}$ is

(a). $\mathrm{z} _{4}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{z} _{2}}{\mathrm{z} _{3}}$

(b). $\mathrm{z} _{4}=\frac{\mathrm{Z} _{2} \mathrm{Z} _{3}}{\mathrm{z} _{1}}$

(c). $\mathrm{z} _{4}=\frac{\mathrm{z} _{1} \mathrm{z} _{2}}{\mathrm{z} _{3}}$

(d). none of these

Show Answer

Answer: (d)ii. argument $\left(\mathrm{z} _{4} /\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}-\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)\right.$ is

(a). $\frac{\pi}{4}$

(b). $\frac{\pi}{3}$

(c). $\frac{\pi}{2}$.

(d). $\frac{2 \pi}{3}$

Show Answer

Answer: (c)iii. For fixed positions of $\mathrm{B}\left(\mathrm{z} _{2}\right)$ and $\mathrm{C}\left(\mathrm{z} _{3}\right)$ all the bisectors(internal) of $\angle \mathrm{A}$ will pass through a fixed point which is

(a). H.M. of $z _{2}$ and $z _{3}$

(b). (a).M. of $z _{2}$ and $z _{3}$

(c). G.M. of $\mathrm{z} _{2}$ and $\mathrm{z} _{3}$

(d). none of these